Aitana Oltra, Frederic Bartumeus and John Palmer, coordinators of the Mosquito Alert platform, have written one of the chapters which highlights the potential of citizen science to study the presence and the expansion of invasive species and vectors of diseases.

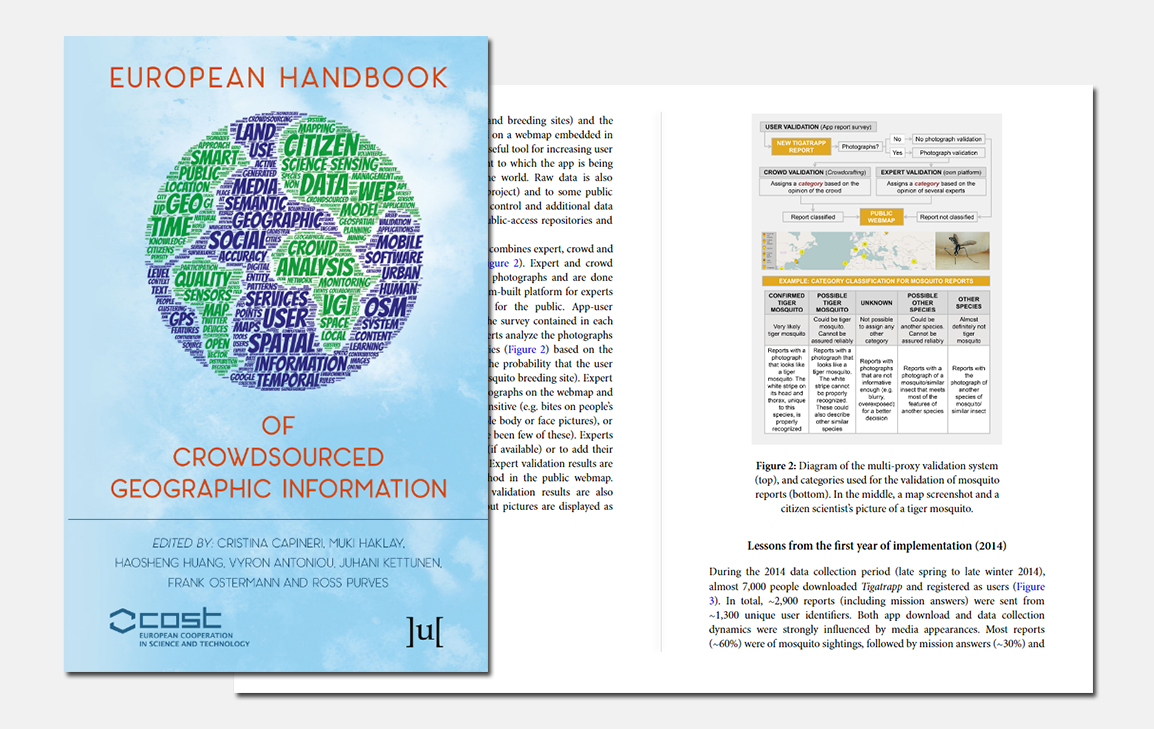

The book has been edited by members of the COST action “ENERGIC” (European Network Exploring Research into Geospatial Information Crowdsourcing), a network of experts that promote activities to explore the potential and the applications of the crowdsourced geospatial information. All the chapters have been written by many scientists from the geographic information area.

As technology grows, a new way to collect geospatial information has emerged. There are more citizens which use websites or apps to send photos or other geolocalized data. Scientists call this new way to collect data as Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI).

The handbook, organized in six parts, analyzes the scientific use of this information and the benefits that it can provide to society. Some authors talk about what really motivate the people to share this kind of information and make it public. Also, it is discussed if inert and static sensors could be replaced by humans. However, there are some limitations of this methodology like privacy and data quality for scientific use.

When citizen participation is a success

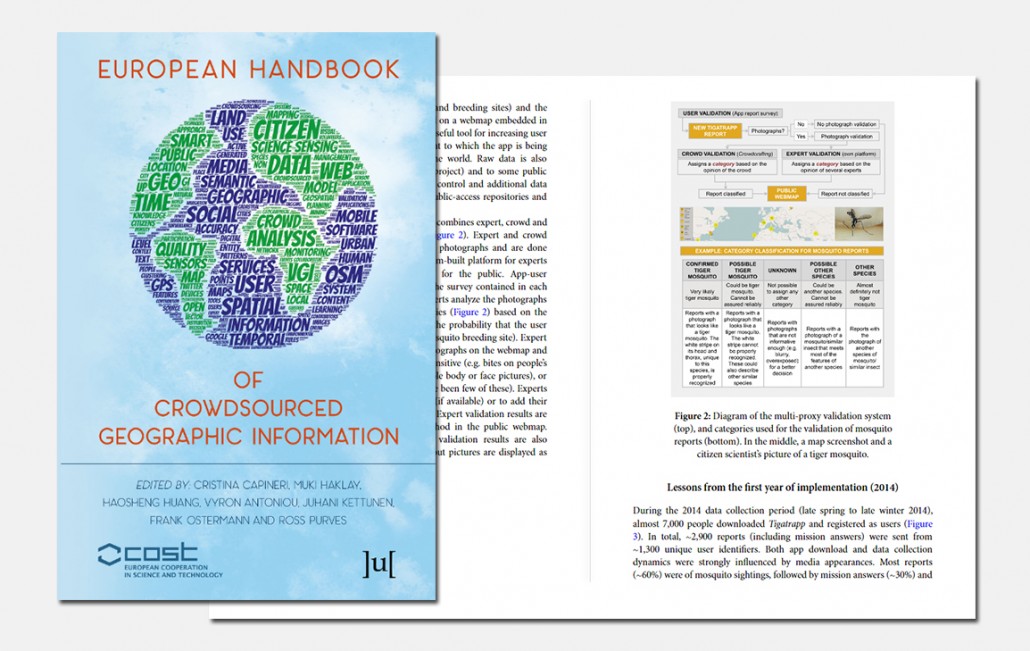

The example of Mosquito Alert (before called Atrapa el Tigre) shows that citizen science can be used to do research, surveillance and control of invasive species which are vectors of diseases, such as the tiger mosquito and the yellow fever mosquito. The chapter focuses on the strategies and criteria that are used to validate the data sent by volunteers, mainly geolocated photos. They also explain how communication has worked with citizens, what kind of scientific research can be done with this information and how it is working with the agents who do the monitoring and control tasks of these species.