Some species of mosquitoes are important transmitters of viral diseases such as dengue, Zika or malaria, to the point of being considered one of the most deadly animals on planet earth. For this reason, many scientific studies have focused on understanding the mosquito-human interaction and, in particular, the sensory responses generated by humans.

Although it is hard to believe mosquitoes not only feed on human blood, in fact flower nectar is their main source of food.

A team of scientists, led by the University of Washington in the United States, has discovered the chemical signals that lead these insects to pollinate a species of orchid particularly irresistible to them. Knowing what you find irresistible could help you develop less toxic and more effective repellents in the future.

Mosquitoes have a very sensitive olfactory system that they use to locate important sources of nutrients, among them the nectar of different flowers or our presence to bite us. While male mosquitoes need nectar to survive, in females the sugar of flowers helps them to increase their life expectancy, survival rate and increase reproduction.

“For male mosquitoes, nectar is their only food source, and females feed on nectar for almost every day of their lives,” says Jeffrey Riffell, professor of biology at the American university

In the study, they examined the neural and behavioral processes of mosquitoes when exposed to flower aromas for which they feel preferences.

- Pollination studies in the orchid species Platanthera obtusata by mosquitoes of the Aedes group.

- Analysis of the floral aromatic compounds that attract various species of mosquitoes.

- Recordings of the electrical activity of mosquito antennas showing how these aromas and compounds are represented and affect their neural activity.

His favorite flower

Some Aedes mosquitoes show affinity for the Platanthera obtusata orchid, being effective pollinators for this species. This association between mosquitoes and orchids provides a unique opportunity to identify sensory mechanisms that help mosquitoes locate sources of nectar.

Platanthera obtusata (Banks ex Pursh) Lindl. 20090624.96 Mount Stearns, Willmore Wilderness, Alberta

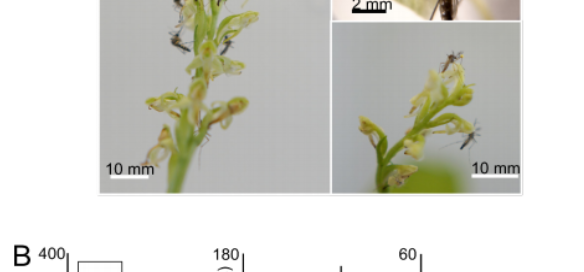

During the study they observed more than 581 Platanthera obtusata flowers during 47 hours, in which they were able to register up to 57 times Aedes mosquitoes feeding on them.

The observations were made in northern Washington state, where the Platanthera group orchids and mosquitoes abound.

Platanthera obtusata has an aroma reminiscent of grass, while other orchids in the environment, which are less attractive to mosquitoes, have a sweeter fragrance. The height and green coloration of the flowers make this plant difficult to distinguish from neighboring vegetation, yet the mosquitoes still manage to orient themselves and zigzag towards their flowers.

When the researchers covered the plants with bags, to prevent mosquitoes from seeing the flowers, the insects kept trying to reach the plants through the bag. This simple experiment made it possible to verify that the orchid generates a great olfactory attraction on mosquitoes, which led experts to analyze the chemical compounds in its aroma.

“The scent is actually a complex combination of chemicals, that of a rose, for example, consists of more than 300, and mosquitoes can detect the different types of chemicals that make it up,” says Riffell.

The orchids of the genus Platanthera differ in their floral essences

Using the gas chromatography and mass spectrometry technique, they analyzed the aromatic essences of six different orchids. They were able to identify a quarantine of chemical products of the different species of orchids of the Plathantera genus, observing that Platanthera obtusata, unlike the others, has a large amount of a compound called nonanal, as well as small amounts of another compound, lilac aldehyde.

The researchers analyzed the reactions of different mosquito species (Aedes canadensis, Culsette sp., Aedes dianteaus and Aedes cinereus) to the identified chemical compounds, by recording the electrical activity of their antennas. Despite the fact that not all native Aedes species reacted with the same magnitude to chemicals, the responses were consistent, leading the team to examine whether other mosquitoes, not native to the orchid habitat, would react the same to their compounds chemicals.

They verified it with Anopheles stephensi, one of the species that spreads malaria and Aedes aegypti that spreads viruses of diseases such as dengue, yellow fever or Zika.

Both Aedes aegypti and Anopheles stephensi were attracted to the scent of orchids when lilac aldehydes were included. But by removing the lilac aldehyde from the aroma, both these species and the native Aedes lost interest in the flower or were repelled by the resulting odor.

Knowing how mosquitoes process complex odors to detect attractive food sources or others, as well as those odors that are repulsive to them could be used in the future to develop more effective repellents.

References:

Lahondère C, Vinauger C, Okubo RP, Wolf GH, Chan JK, Akbari OS, et al. The olfactory basis of orchid pollination by mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:708–16