A study of the genetic composition of the tiger mosquito in Europe detects the different entry routes from Asia and how its invasion is determined by the road network. The results confirm the importance of the mosquito displacement inside the cars previously described by Mosquito Alert researchers. The movement of mosquitoes between regions determines their genetic composition and may have important implications such as the existence of differences between mosquitoes in their effectiveness when transmitting viruses such as Zika, dengue or Chikungunya.

Fig. 1. Adult of tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus. Author: Mosquito Alert CC-BY

Early September 2007. Tiger mosquitoes fill the pages of newspapers. For the first time in its history, Europe experiences an outbreak of Chikungunya. The days pass and in the end 217 autochthonous cases of infection are confirmed. All of them in the Italian province of Ravenna. It is suspected that the virus causing the disease probably came through an infected traveler. But how could a tropical disease spread in Europe?

Because the Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is native to Africa. It was first detected in Tanzania in 1952, from where it later spread through South Africa, Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia, Senegal, Uganda, Nigeria and Angola before jumping into Southeast Asia. In the following decades it appeared in Thailand, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, India and Malaysia. And already in the 21st century the disease broke into the Indian and African islands.

However, the Italian outbreak of 2007 was an important step forward. It was the first one that took place in a temperate zone, taking the disease beyond the tropics. But it was not the only one. In 2010 another one took place in the south of France, in 2014 a new one was detected in Montpellier, although these were only a few isolated cases, and in 2017 one more around Rome.

In a globalized world, with more and more leisure trips, the arrival of people infected with the virus from the tropics to Europe is constant, but for an outbreak like Italy to take place, another actor is needed, a mosquito capable of transmitting the virus among people. The Italian region of Ravenna, the south of France, Montpellier and the region of Rome have one thing in common: the tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus (Fig. 1), is established there.

The tiger mosquito, originally from Southeast Asia, is capable of transmitting the disease. A tiger mosquito that stings an infected tourist after returning from his trip through the tropics can transmit the virus to new people. In Italy the origin was in an infected tourist who returned from his trip to India. In Montpellier it was a person who returned from a trip to Cameroon. The tiger mosquito did the rest.

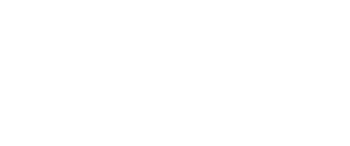

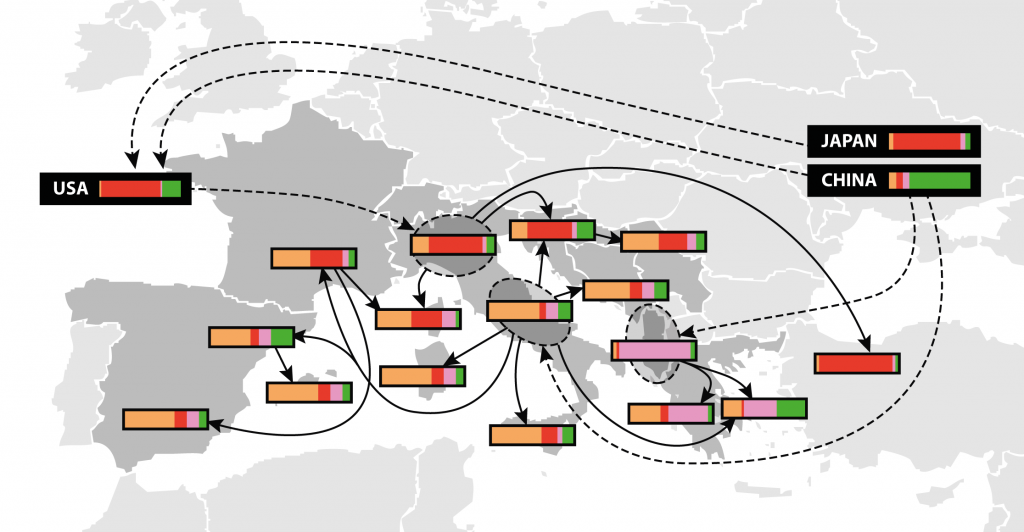

Fig. 2. Map with the three routes of introduction of tiger mosquito in Europe from China and Japan via the United States (dashed lines). The solid lines indicate the movements of the tiger mosquito within Europe. The bars represent the genetic composition of the populations studied. Modified from the original Sherpa et al. (2019) Molecular Ecology, by J.Luís Ordoñez (CC-BY-NC-2.0)

The tiger mosquito came to Europe by boat from China and the United States

The tiger mosquito is what in biology is known as an invasive species. A species that, once it has been introduced in a place, outside its original distribution area, is capable of developing and expanding. Until not long ago, the tiger mosquito was restricted to Southeast Asia, its area covered from Indonesia to Japan. However, in recent decades humans have helped colonize all continents except Antarctica. A new study published in the journal Molecular Ecology has just revealed what routes the tiger mosquito used to enter Europe. It is a genetic study carried out by researchers from the University of Grenoble, for which they have analyzed 692 mosquitoes from 109 different localities. Although they did not participate directly in the study, experts from Mosquito Alert, Sarah Delacour, Mikel Bengoa and Roger Eritja, contributed to the work by providing to the French researchers with part of the mosquitoes analyzed, with specimens captured in Andalusia, the Balearic Islands and Catalonia. From the genetic data obtained they have been able to determine that the tiger mosquito entered three points in Europe from three different places (Fig. 2).

The first introduction took place in Albania in 1979. It was in a tire warehouse in the Albanian city of Lac where they were detected for the first time. Genetic studies suggest that mosquitoes arrived from China, through maritime trade.

A decade later, in summer of 1990, tiger mosquitoes were once again detected in Europe, this time in Italy. But the mosquito did not arrive in Italy from Albania, not only from Asia, but from the United States. Apparently, the species reached the city of Genoa first, and Padua in 1991, through the maritime trade of used tires that this city maintained, and maintains, with Atlanta. To the United States the mosquito had arrived shortly before, in 1985, once again hidden among tires from Japan (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Used tires, the main transport route of tiger mosquito from Asia to Europe and an important breeding point. Cars: Pixabay License

Already at the gates of the new century, the study suggests that new mosquitoes landed in Italy, probably from China. This time they did it in the center of the country, where they mixed with the tigers of American-Japanese origin, which came down from the north.

These three entry points are the original source of the tiger mosquito in the rest of Europe. Although we do not get to know exactly the moment and the cause of the introductions, with the genetic analysis it is possible to trace the history of the different introductions and discover the routes of dispersion of the species. What the genetic study confirms is that the mosquito has limited dispersal capacity by itself, and that we humans transport it without realizing one place to another.

We are the accomplices of its expansion

In fact, the genetic composition shows that the dispersion of the tiger mosquito fits perfectly with the topology of human communication networks: ships, trains and roads. The genetic study reveals population similarities in some regions that would indicate the road movement of the species. Mosquitoes introduced into Albania have expanded into the Balkans, reaching Greece, Montenegro, Bosnia and Serbia, but they do not seem to have left that region yet. On the other hand, mosquitoes introduced in northern Italy have reached Slovenia, Croatia, Switzerland and northern France. In southern France and Spain, it seems that there is a mixture of mosquitoes from two Italian foci: the one introduced from China and the one from the United States – Japan.

The results of the study published in 2017 by Mosquito Alert project researchers better illustrate the human mechanisms that the tiger mosquito uses to move to short and medium distances. In this work it was demonstrated how the accidental transport in cars contributed to the dispersion of the mosquito through the Spanish territory. The study estimated that between 12,000 and 71,000 cars circulate in the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona each summer with a tiger mosquito inside. The investigation revealed how mosquitoes move from one province to another as stowaways inside our cars.

The mosquitoes of Spain do not have a single origin

But this transfer of tiger mosquitoes not only occurs between municipalities and provinces of Spain but goes further. The analysis reveals that mosquitoes from central Italy arrived first to Spain. They were detected for the first time in 2004 in the Catalan municipality of Sant Cugat del Vallés. How it came to Barcelona is difficult to secure, because the options from Italy are many by sea or land. In any case, it was a passive dispersion using a human transport, probably by land transport of road merchandise, which in general coincides with the later expansion of the species that appears along the great roads.

However, it may be that along the Mediterranean coast the mosquito has not expanded exclusively following the coastal highway and jumping to the Balearic Islands by ferry. The genetic analyzes show a more complex reality. Not all the mosquitos of the Spanish Levant have their origin in the Catalan populations, some mosquitoes have arrived directly from the south of France, where in turn they arrived from the north of Italy, which in turn came from the United States, and these from Japan.

Multiple introductions are frequent in invasive species, and this reminds us that after Sant Cugat, the next town, detected one year later, was Torrevieja, in Alicante more than 500 km away.

The expansion of the tiger mosquito and its genetic composition are not understood without knowing the routes of commercial transport and the displacement of tourists from north to south. The movement of mosquitoes within the Iberian Peninsula follows that of human movements, with large displacements between cities from where they would reach the smaller municipalities around them. In the Iberian northeast it seems that mosquitos arrived from different parts of Europe, which in turn come from different parts of Asia, have come together, coincided and mixed.

This mosaic does not only have a theoretical interest, because the origin and the genetic composition of the mosquitoes that live in our locality can imply different efficiencies when transmitting the viruses, or resisting the insecticides. This is superimposed on the continuous evolution of both the insects and the viruses themselves, which has a great relevance in public health and in the control of diseases.

The transfer of mosquitoes increases their genetic diversity and their success as an invader

As a general rule, populations of invasive species originate from the introduction of a few individuals. This phenomenon is known as the “founder effect” giving rise to populations with little genetic diversity. These genetically impoverished populations are more susceptible to a pathogen, and even to insecticides in the case of mosquitoes.

However, in the case of the tiger mosquito, this constant mosquito mixture facilitated by transport increases the chances of mosquitoes crossing from different populations. In this way, it can easily occur that a mosquito arrived from Italy crosses with one arrived from France. The crossing between both will give rise to new genetic combinations that did not exist in their populations of origin, thus increasing the genetic diversity of the population. This is a clear advantage for them and an additional problem for us, because the greater genetic diversity implies more capacities to adapt to the new habitats that colonize, for the transmission of diseases and even to develop resistance to insecticides.

International flights and local mosquitoes: the perfect storm

The presence and extension of the tiger mosquito in Spanish territory raises the threat of tropical viruses such as Chikungunya, but also Zika and dengue. Until recently, these pathogens were unique to tropical regions such as Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa or Southeast Asia, but the increasing number of international trips facilitates the virus to reach Europe. In Catalonia alone, in 2018, 7 cases of Chikungunya, 24 cases of Zika and 71 cases of dengue fever were confirmed. All cases contracted the virus abroad before returning to Catalonia, without a doubt, the increased circulation of people, together with the presence of a mosquito capable of transmitting the virus raises the risk of an outbreak like the one took place on 2007 in Italy.

References:

Eritja, R., Palmer, J.R., Roiz, D., Sanpera-Calbet, I., & Bartumeus, F. (2017) Direct Evidence of adult Aedes albopictus dispersal by car. Scientific Reports 7, 14399

Jané, M., Martínez, A., Torner, N., Maresma, M. (2019) Casos de malatia per virus Chikungunya, Dengue i Zika a Catalunya. Agència de Salut Pública de Catalunya. Generalitat de Catalunya. 10pp

Manni, M., Guglielmino, C.R., Scolari, F., Vega-Rúa, A., Failloux A.B., Somboon, P., Lisa, A., Savini, G., Bonizzoni, M., Gomulski, L.M., Malacrida, A.R., & Gasperi, G. (2017) Genetic evidence for a worldwide chaotic dispersion pattern of the ardovirus vector, Aedes albopictus. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 11, e0005332

Paupy, C., Delatte, H., Bagny, L., Corbel, V., & Fontenille, D. (2009) Aedes albopictus, an arbovirus vector: from the darkness to the light. Microbes and Infection 11, 1177-1185

Sherpa, S., Blum, M.G.B., Capblancq, T., Cumer, T., Rioux, D., & Després, L. (2019) Unravelling the invasion history of the Asian tiger mosquito in Europe. Molecular Ecology, Early View 29 April 2019

Sherpa, S., Rioux, D., Pougnet-Lagarde, C., & Després, L. (2018) Genetic diversity and distribution differ between long-established and recently introduced populations in the invasive mosquito Aedes albopictus. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 58, 145-156

Zeller, H., Van Bortel, W., & Sudre, B. (2016) Chikunguya: its history in Africa and Asia and its spread to new regions in 2013-2014. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 214, S436-S440

Spanish News:

Espiño, I. (2007) El chikungunya: ¿un riesgo para Europa? El Mundo. 24/09/2007

Sáez C. (2017) Por qué en España es improbable que se produzca un brote de chikungunya como en Italia. La Vanguardia. 19/09/2017

de Benito, E. (2007) La enfermedad de chikungunya sale del Índico y se asienta en Italia. El País. 07/09/2007