Summer, Barcelona 1821. Two centuries ago the city was also confined. It closed its walls and accesses to the metropolis. The political and administrative authorities fled from her. They installed the capital of Catalonia in Esparraguera while preventing people from leaving. An epidemic had spread through its streets.

It all started at the end of June. On the 29th of that month, the brig El Gran Turco docked in the port. She came from the other side of the Atlantic, from Havana, having made a stopover in Malaga before continuing to the city of Barcelona. The port authorities could not suspect what his arrival would unleash. Once in port, a group of shipyard workers got on the ship to caulk its hull, inserting a combination of tar-soaked hemp tow between the wooden boards to prevent water from entering between the grooves. Those people were to be the ones to spread the disease that had traveled aboard the ship through the streets. Just a few weeks later, many people with symptoms appeared in the Barceloneta marine district.

The doctors summoned by the municipal authorities debated at first what disease they were facing. Some opted for an outbreak of tuberculosis, very frequent then in the city. Others that it was “black vomit”, the name by which yellow fever was known in Spain. In the end the second option prevailed. Barcelona was facing an outbreak of yellow fever. One that would kill thousands of people in the next few months. Some have even estimated that 6% of the population perished in that episode.

Yellow fever, an unknown disease

Yellow fever was a mysterious disease. Its symptoms were known. It had been ravaging tropical regions of America and Africa for years. Even Europe had suffered its effects throughout the 18th century. In 1730 he reached various cities in Portugal, Spain, France, Italy, and even places as unlikely and far from the tropics as northern Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Russia. In the 19th century the outbreaks continued to occur on the continent: Brest in 1802, Cádiz in 1800, 1804, 1014 and 1819; Gibraltar in 1810 and 1813; Malaga in 1803, 1804, 1813 and 1821; Seville in 1800 and 1804; Murcia and Cartagena in 1804 and 1810; Tortosa, Palma de Mallorca, Malaga and Barcelona suffered in 1821. The coastal cities of the Iberian Peninsula were the most affected. Those that received ships with sailors and merchandise that arrived from America where outbreaks were frequent. Despite the knowledge and experience of the disease, little was known about her.

Fig. 1. Representation of the yellow fever epidemic in Barcelona in 1821 by the Frenchman Nicolas-Eustache Maurin. Source: Historical Archive of the City of Barcelona (AHCB 04544).

There were still decades to go before it was discovered that it was a viral disease. Although the word “virus” comes from the Greek and means “toxin”, the ancient Greeks never knew of its existence. The first virus was not described until 1899. It was the tobacco mosaic virus identified by the microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck. Nor was it known that the infectious agent, regardless of its nature, was transmitted by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. The involvement of mosquitoes did not arise until 1881, the year in which Cuban doctor Carlos J. Finlay proposed the yellow fever mosquito as a transmitting agent. Years later, doctors from the US army, concerned about the losses that the disease caused in their troops during the war in Spain and the United States, demonstrated their hypothesis. But none of this was known when the disease entered Barcelona that summer of 1821.

Among the medical community there was another conflict. The classical school considered it to be a contagious disease. Although viruses were not known to exist as organisms, contagion was believed to occur when there was an exchange of physical or chemical agents between a sick person and a healthy person. For others the transmission of yellow fever did not fit into this scheme. In the same outbreak, patients appeared in an area at a considerable distance from each other, and without there having been contact between them. It was not considered that the mosquito or any other animal could transmit it, so the school of anti-pollution doctors advocated a local origin of the disease. They denied that the disease had arrived on board El Gran Turco or any other ship, but instead had to look in the Rec Comtal, the canal that crossed the eastern part of Barcelona, the cause of the disease. The poor condition of their water, which received the waste from the municipal slaughterhouse and from various factories before unloading at the port, was the source of infection. The disparity of scientific criteria that always occurs when faced with something unknown. We have lived it in the COVID19 pandemic, about whether it is transmitted by droplets or aerosols, and the health and political measures to take. In the end, time proved right to those who considered in 1821 that they were facing a contagious disease, but this technical dispute ended up aggravating the disenchantment of the population with the health authorities and their measures.

Other epidemics, same human beings

In August, as soon as the disease overwhelmed the Barceloneta neighborhood, the district was ordered to be confined to prevent it from spreading to the rest of the population. The isolation did not work and in October a sanitary cordon had to be created around the entire city. The restrictions gave rise to reactions among the people and the media of the time, circulating among the inhabitants hoaxes that are not far from those we have heard throughout the COVID19 pandemic. In the 21st century it has been said that vaccines contain microchips and other various things, to manipulate us or make us sick, two centuries ago, it was said that doctors killed the sick with poison. The belief was such that there were those who refused to take the drugs for fear that they would harm their health. Or they refused to transfer the sick to the places enabled for their care. In two hundred years, neither the fears nor the lies have changed. We remain the same, new epidemics will come and we will remain the same.

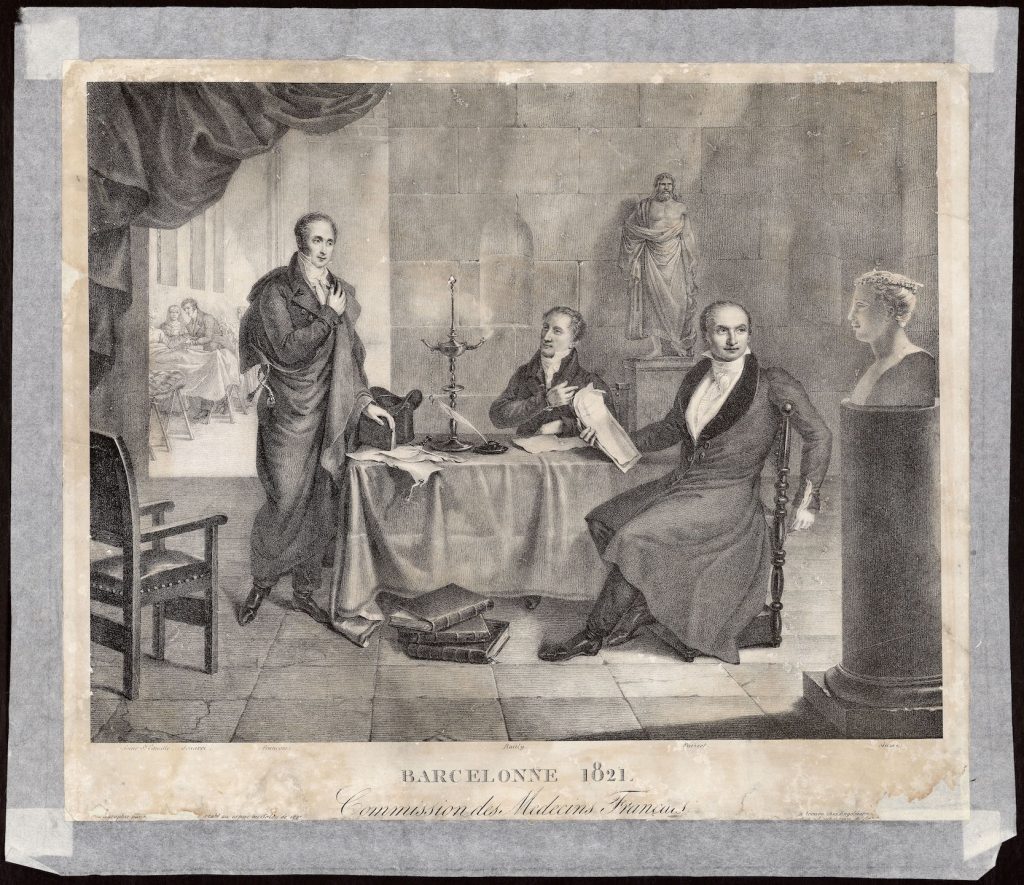

Fig. 2. The 1821 epidemic caught the attention of English and French physicians. Some, like those depicted in Claude-Jean Besselièvre’s engraving, came to the city to study the phenomenon in situ. Source: Historical Archive of the City of Barcelona (AHCB 18437).

The corruption that took place during those months did not help to calm or resolve the climate of distrust. The patency of the sanitary cord was variable. You could cross it or not depending on the coins you had. Rich people were the first to flee the city. As did politicians and rulers. For three months, the political and administrative capital of Catalonia moved to Esparraguera, a municipality located at the foot of the Montserrat mountain range, far from the coast and the epidemiological outbreak. The flight of the administration and the economic crisis brought about by the sanitary blockade of the city accentuated the discontent of the citizens trapped within the walls. In the end, people were allowed to go out and settle in tents and barracks on the slopes of Collserola and Montjuic. Beneath them the walled city and the epidemic wasting away. The nightmare came to an end at the end of November. Time when mosquitoes stopped. The cold took away the mosquitoes and the disease. The outbreak faded and the city organized a procession in honor of the Virgen de la Mercè in December for her supposed work against yellow fever. After the storm, life returned to normal. However, in 1870 yellow fever would return to the city.

The #MosquitoAlertBCN project in which CREAF, UPF, Irideon and the Barcelona Public Health Agency (ASPB) participate, and which have the support of the Barcelona City Council and the «la Caixa» Foundation, works to make Barcelona a city intelligent in the fight against the tiger mosquito and the diseases it transmits, allowing you to anticipate problems.

References

Bernat López P. 1998. Las posiciones anticontagionistas ante la epidemia de fiebre amarilla de Barcelona en 1821. Estudios de Historia de las Técnicas, la Arqueología Industrial y las Ciencias 1998: 899-906

Gaspar García MD. 1992. La epidemia de fiebre amarilla que asoló Barcelona en 1821, a través del contenido del manuscrito 156 de la Biblioteca Universitaria de Barcelona. Gimbernat 18: 65-72

Ortiz García JA. 2017. Autoridad e imagen de la epidemia. La fiebre amarilla en la Barcelona del siglo XIX. Potestas 11: 93-110

Romero Marín JJ. 1992. Medicina y actitud popular. La epidemia de 1821 en Barcelona. Gimbernat 18: 97-100