When a mosquito bites us, an itchy welt usually appears where the female mosquito has pierced our skin to suck a little blood with which to feed. This welt usually disappears in a few days.

Sometimes, however, a mosquito bite causes inflammation, pain and irritation in a larger area that leads us to scratch and even cause small wounds. As a general rule, their bites do not cause excruciating pain, but we are all aware that when several mosquito bites come together at the same time they can make us have a bad day.

But why do their bites bother and irritate? Do we really understand what happens when a mosquito bites us?

In fact, mosquitoes are much more complex than most of us realize.

How do mosquitoes bite us?

To survive, mosquitoes, both male and female, feed on plants and flowers, they obtain sugars that provide them with enough energy to carry out their basic activities, but when it is time to reproduce, females need extra energy for the development of the eggs. This energy is obtained from the blood, rich in proteins that allows the development of their eggs. In this way, the taste system and, above all, the olfactory system are crucial for the survival of mosquitoes in the environment. They help them identify and locate their food sources.

Both to pierce the stem of a plant and to suck blood from an animal, mosquitoes have a system called a biting-sucker formed by a stylet or proboscis that allows them to pierce and then suck the fluids.

The stylet is normally kept within a sheath formed by the lip, which protects and hides the rest of the mouthparts. When the mosquito lands for the first time on its potential victim, its pieces are still completely protected, the individual palpates the skin with the tip of the lip several times until they find the most suitable place to bite. This is usually the closest to a blood vessel.

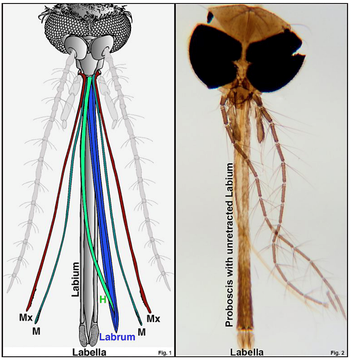

The tip of the lip remains in contact with the victim’s skin, acting as a guide for the rest of the mouthparts, and it folds as the rest of the mouthparts pass through the skin. In order to surgically pierce their prey, mosquitoes have 6 mouthparts: 2 jaws, 2 maxillae, the hypopharynx and the labrum.

Fig 1. Young-Moo Choo, Garrison K. Buss, Kaiming Tan, Walter S. Leal Front Physiol. 2015; 6: 306. Published online 2015 Oct 29.

The jaws are used to pierce the skin. The jaws are pointed while the maxillae are leaf-shaped and serrated. To introduce them, mosquitoes move their heads back and forth.

The hypopharynx and labrum, on the other hand, are hollow, acting as a tube. Through the hypopharynx they inject saliva with a very powerful anticoagulant protein. This protein prevents platelets from forming a clot, thus ensuring that the blood does not stop flowing while they ingest it. The labrum is the channel through which they suck blood and, therefore, feed. In fact, the mosquito is able to filter the red cells from the plasma and get rid of the water, thus leaving more space to store the nutrients from the blood in the abdomen.

Ribeiro JM, Francischetti IM (2003). “Role of arthropod saliva in blood feeding: sialome and post-sialome perspectives”. Annual Review of Entomology. 48: 73–88. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.48.060402.102812. PMID 12194906.

Valenzuela JG, Pham VM, Garfield MK, Francischetti IM, Ribeiro JM (September 2002). “Toward a description of the sialome of the adult female mosquito Aedes aegypti”. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 32 (9): 1101–22. doi:10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00047-4. PMID 12213246.

Vogt MB, Lahon A, Arya RP, Kneubehl AR, Spencer Clinton JL, Paust S, et al. (2018) “Mosquito saliva alone has profound effects on the human immune system”. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12(5): e0006439. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006439